Introduction to Compassionate Systems

AUTHORS | CONTRIBUTORS

[The following material has been re-formatted as a separate article] [DRAFT]

The Fundamentals of Compassionate Systems

Peter M.Senge

August 6,2021

The education renaissance is fundamentally about school that is grounded in the changing needs of the world and in a genuine commitment to human learning and development. It is not about the new one correct new model for education. That said, our own effort to contribute to this renaissance has arisen from a particular synthesis of systems thinking, social-emotional learning, and mindfulness and contemplative practice. – what we have come to call it the compassionate systems framework. It is anchored in a central idea of profound inter-connectedness, that all life arouses within webs of inter-dependence, including us.

Practically speaking, the compassionate system approach is grounded in tools and practices that have been developing for many decades. It is one thing to espouse systems thinking or compassion or the importance of reflection. It is another to be able to do it, especially amongst the stresses and emotional challenges of today’s world. We must be able to engage with the complexities and human tragedies of today’s reality life without getting emotionally overwhelmed by them, to see the forces at play that influence people’s feelings, thoughts and actions, and to develop relationships, strategies and practices that can help shift them. This is what it means to cultivate compassion as a systemic property of mind.

Last, this cannot be done without facing the core structural challenge of all deep change in education. The vast majority of the adults who teach and manage schools themselves lack skills like systems thinking and collaborative learning. As a system designed and run by adults, how do you ever sustain deep change that requires capacities that the adults, themselves the products of the traditional system of education, never had the chance to seriously develop? This is the primary reason why systems of education tend to conserve their own traditions, even when those traditions are seriously out of touch with what is needed for the future. It is also why any serious change strategy must involve capacity building that focuses on adults and students equally and leave behind the “teacher as expert” culture of traditional schools, as well as engaging the adult work cultures across the education hierarchy beyond schools themselves. We are all in this together.

The Essence of Systems Thinking

Systems thinking is a modern way of acknowledging and working with a very old idea: profound inter-dependence.

“If you are a poet, “ writes the Buddhist monk and teacher Thich Nhat Hanh in his essay Interbeing, “you will see that there is a cloud floating in this piece of paper. Without a cloud, there can be no rain; and without the rain, the trees cannot grow; and without the trees, there can be no paper… so we can say that the cloud and the paper inter-are.”

(For those of us reading this on an electronic device, we can say the same about the ore and oil that were mined to produce the metal and plastics out of which the device was made and the extraordinary pressures, over millennia, by which the earth produced them, and the creatures that lived long ago who, after their bodies had returned to the earth, became the fossils from which the oil was created. Paraphrasing Thich Nhat Hanh, we could say, “the long-ago creatures, the minerals, and this device also inter-are.”)

The passage continues:

And if we continue to look, we can see the logger who cut the tree and brought it to the mill to be transformed into paper. And we see the wheat. We know that the logger cannot exist without his daily bread, and therefore the wheat that became his bread is also in this sheet of paper. And the logger’s father and mother are in it too. When we look in this way, we see that without all of these things, this sheet of paper cannot exist…

Look even more deeply, we can see we are in it too. When we look at what is written here, it is part of our perception. Your mind is in here and mine is also…

This is why I think the word inter-be should be in the dictionary. ‘To be’ is to inter-be. You cannot just be by yourself alone.

The Epistemology of Systems Thinking

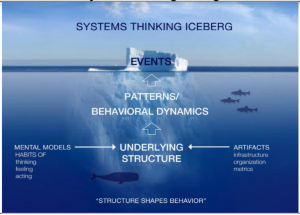

The field of system dynamics, as it originated at MIT, teaches that systems thinking starts by looking below the surface at the deeper sources of change. This involves a specific shift in focus from isolated ‘events’ to longer-term patterns of change and to the deeper underlying systemic (inter-dependent) structures that generate and shape those patterns. The systems thinking iceberg diagram, shown in Exhibit 1, metaphorically represents these different levels from which we can view the world. Developing as a systems thinker means to practice moving up and down the iceberg, and especially inquiring into underlying structures.

Each of these ways of explaining reality has merit, but they differ in the degree to which they enable change. At the event level, all you can do is react, and organizational cultures anchored at this level foster climates of continual “fire fighting.” At the pattern level, you can see trends and are more able to adapt. But only at the level of underlying structures do you start to appreciate the forces that shape change and how they might shift.

Sadly, most of us, most of the time, are firmly tethered to the event level. Today, the increasing intrusion of media in all aspects of our lives means that we are deluged with information about events. There is nothing inherently bad with focusing on events; if you step out in front of an approaching bus, it is not a good time to ponder the arc of your life.

But our brains have not evolved to deal with the amount of information we are immersed in, and it’s easy to feel overwhelmed and be hijacked by our emotional responses to events, leading to getting burned out and losing all focus on the deeper levels of change. Social media combines our tendency to focus with events with our orientation toward inter-personal communication such as with peers and people close to us. The result is one more layer of events to attend to, in the form of messages. The Yankelovich media research firm estimated in 2007 that the average person living in a city sees 5,000 messages per day, most of them through electronic media. No wonder the flow of events has so much cognitive force.

But the capacity to look across all levels of the iceberg can be rehabilitated with practice.

(3300)

Deeper Aspects of Systems

The next step in moving to a deeper level, below the present-day fixation on events, is to become aware of broader patterns. Events do not exist on their own; they are part of broader trends that change over time. Some factors get stronger, others get weaker, and still others level off, or change direction. These patterns, individually or through the interplay among them, determine the way an individual event plays out.

One example of a broader pattern is the growing penetration of media and messages itself. In the 19th century, the number of messages seen per day by a city dweller was limited to a local newspaper, street signs, posted notes, and shop windows: probably less than 200. Then the communication devices in everyday life proliferated: starting with mass-printed publications, radio and motion pictures, then television, and then the internet and hand-held devices. By the 1980s, according to Yankelovich, an average urban dweller would see 2,000 messages per day. The figure kept rising, probably exponentially: if it was 5,000 in 2007, it is probably twice that amount by now, unless there is simply an innate limit because of the time and attention available to a person in a day.

This trend, the pattern of media proliferation over time, is just “below the surface” in the iceberg metaphor. Few people notice its impact. But when your attention is called to it, with just a bit of effort, you can see the trend and recognize its effects on human stress, anxiety and uncertainty.

You can also look a little deeper, to the level of behavioral dynamics. These are the ongoing factors that generate the patterns as they interact. Behavioral dynamics involve systemic factors, such as long-standing habits, the activities of businesses, universities, and governments, biological and climate-oriented changes, and political, economic and social forces..

Consider the inter-dependent forces at play that have led to the increasing intrusion of media. One force is the business models of mass media and social media enterprises. Despite their many differences, they are all oriented to maximizing the hold on peoples’ attention. Over time, not surprisingly, both types of enterprises have become increasingly sophisticated. They have found many cognitively and emotionally gripping hooks that make the latest “breaking news” seem ever-more compelling. As they become more effective, the media companies build financial power, allowing them to invest even more in finding ways to grab our attention.

And media companies are not the only factors generating these behavioral dynamics. There are the increasingly sophisticated array of physical devices that make it ever-easier for people to pay attention to media, and ever-harder to resist. Since 2007, as just one example, the annual release of the latest i-phone has been a major social event. People celebrate it as an upgrade in the new management system of our attention span.

Of course, we ourselves are also intimately tied to shaping these behavioral dynamics, especially as we become more entwined with this system and feel its effects. There are important correlates between the levels of the systems thinking iceberg and brain dynamics. The area of our brains that analyzes and processes information about patterns and engages in reflection and analysis, centered on the prefrontal cortex, is well suited for understanding the slower dynamics of the lower levels of the iceberg, patterns and underlying systemic structures. But it moves much more slowly than the limbic system, the part of the brain that reacts to events and is the seat for the associated emotions. In the event-oriented modern world, with its obsession with rapid action, the time and space to slow down and think more deeply has become an ever scarcer resource.

One reason contemplative practices have become so central in the work of the Center for Systems Awareness is that regular practice strengthens connections between the emotional brain and the thinking brain, making it easier to observe events and not be hijacked by them. But individual contemplative practice needs reinforcement in daily life: for example, in work and social environments that create space for quiet and deeper conversation. We also need new structures linking personal practice and social reality. All this, is, if anything, even more important for children and young people, whose natural sensitivity to their environment place them at risk of event hijacking. They are typically just learning how to shape their social spaces during their school years, and all too often they take their cues from the adults around them.

Many people understand this. But why is it so difficult to put these new environments into place? Because of the underlying “structures,” as we call them, that become evident when you focus still “deeper” down the iceberg. It takes a bit more determination and patience to explore this murky and inherently indistinct territory. But when we do, we start to understand real systems change as shifts in both the artifacts and corresponding mental models that shape underlying structures.

Artifacts are the more tangible aspects of the structures that affect us. These include rules, metrics, policies, explicit processes and practices, organization structures, and (in a digital sphere) aspects of computer code and software design. Some people use the term “systems change” to refer to changes in these artifacts: for example, changes in a policy framework or an IT installation. But this misses a major element: the underlying mindsets, assumptions and paradigms entangled in culture that has shaped these artifacts.

In America and many other places, we are all living through a painful illustration today, related to racism. America has been creating policies to support African-American rights for a century and a half, going back to the Emancipation Proclamation. Yet racism persists, driven by underlying mental models that themselves reflect views of humanity.

Many of us hold a naïve belief that change in formal policies and laws, in itself, will be enough to change the system. The civil rights experience shows otherwise – and also how hard the shift will continue to be. Not only is change in mental models slower than change in formal rules, but it easily generates resistance. People become emotionally invested in protecting themselves and others from implications and ideas that counter their own views, especially their deeply-held, unvoiced views. Most of us would also rather not admit these deeply held mental models, which then gives them even greater power in times of stress and anxiety. In 2020, humanity found itself in a perfect storm for racism: a global pandemic, arising in an event-hijacked culture, which would rather not talk about underlying attitudes it is invested in denying, with some structures — like police practices, the increasing use of video to document events, and the polarization of people on social media – that exacerbate the tension.

It takes time (and often some collective insight) to digest and diagnose the patterns of systems change in terms of artifacts and mental models. The very words “system” and “structure” can focus our attention only on events outside of ourselves. But, the systems worldview means little if we do not see ourselves as connected to the system we are studying, and part of the forces shaping how it functions. The “system” is not just outside us. It also lives inside of people, in the mental models we have acquired and internalized from living within the system. Change in artifacts and mental models are equally important, and effective change strategies must attend to both. As Walt Kelly’s famous comic strip character Pogo said many years ago, “We have met the enemy and they is us.”

(4600)

Compassion

There is a simple English word that expresses this lived experience of profound inter-connectedness: compassion. Mette Boell points out that the roots in Latin and Greek (com meaning “with” and passion from pathos meaning suffering) mean “standing with” the suffering or experience of the other. But the meaning of “compassion” is broadening, today, to mean a deliberate act of identification with, and commitment to, another person’s felt experience.

Compassion often gets confused with words like sympathy and empathy. The former expresses the emotion of sadness for the plight of another; it often suggests a subtle distancing of ourselves, as if we are standing above and looking down at someone we feel sorry for. Empathy comes from the German einfuhlen, literally to “feel into.” Today, cognitive scientists recognize empathy as an innate human capacity, one we share with many social species. It is neither good nor bad. To bully another person requires that we have a feeling for what is painful to her or him – otherwise we have no idea how to do it effectively. By contrast, in many religious traditions East and West, compassion is considered a cultivated capacity that builds on our innate empathy and adds intentionality. One works over time to get better at “being with” the suffering of the other without being taken over by the other’s emotions – and to cultivate an intention for the other’s well-being.

Today, it is common for educators to talk of having “compassion burnout.” By these definitions, this is really “empathy burnout.” This is not just a matter of semantics. Learning how to build the capacity for compassion so that we are not overwhelmed by the suffering of others and yet also do not emotionally disconnect from the other may tell the tale of how our societies navigate through times of crisis like today.

The extremism arising around the world today can be seen as very human reactions to the fear, pain and anger evoked by circumstance people find themselves and others trapped within. The compassionate systems perspective offers an antidote of sorts, pointing to the need to both understand the deeper or systemic sources of problems and to also stay connected to the experience of all of us caught in those forces – including ourselves. It helps us understand that we are neither blameless by-standers nor helpless victims, and that real systems change, paradoxically, is a deeply personal journey – an understanding that is bedrock for the types of leadership needed now at all levels in shepherding the learning Renaissance.

“In the end, the only thing I can really control is how I show up,” says Michael Funk, the State Director of “expanded learning” (programs that occur outside of school, like summer- and after-school programs) for the California State Department of Education. “This is why we try to start all meetings today with a few quiet moments of mindful reflection so that people can check in with how they are right now and reflect on their deeper intentions for the work they are about to do.” “Once we starting to share the compassionate systems tools with the young people with whom we work,” says Michelle Francois of the National Center for Youth Law, “they started to help us understand how our own state of mind and emotion have been distancing us in ways we never understood. As one young man explained it, ‘The people trying to help me are so stressed, I never tell them a lot of what is really happening. It’s weird, but I realize that I was managing the emotions of those who were trying to help me.’ It never dawned on us that our inability to handle our own empathic distress was so limiting our effectiveness.”

(5200)